Flat Earth: The Strange Persistence of a Fringe Belief

The belief that the Earth is flat-a notion long abandoned by mainstream science-continues to capture imaginations and fuel controversy. Why does this strange idea refuse to die, even in the era of satellites and instant communication? The answer is a story of ancient myth, Victorian obsession, viral videos, and the stubborn power of community.

Ancient Origins

For much of human history, civilizations pictured the Earth as a flat surface, often surrounded by a cosmic ocean or falling off into nothingness. Ancient Egyptians, Mesopotamians, and early Greeks imagined the world as a disc beneath the sky. It wasn't until thinkers like Aristotle observed the curve of the Earth's shadow on the Moon that the round Earth theory took hold.

The Rise of Modern Flat Earth Societies

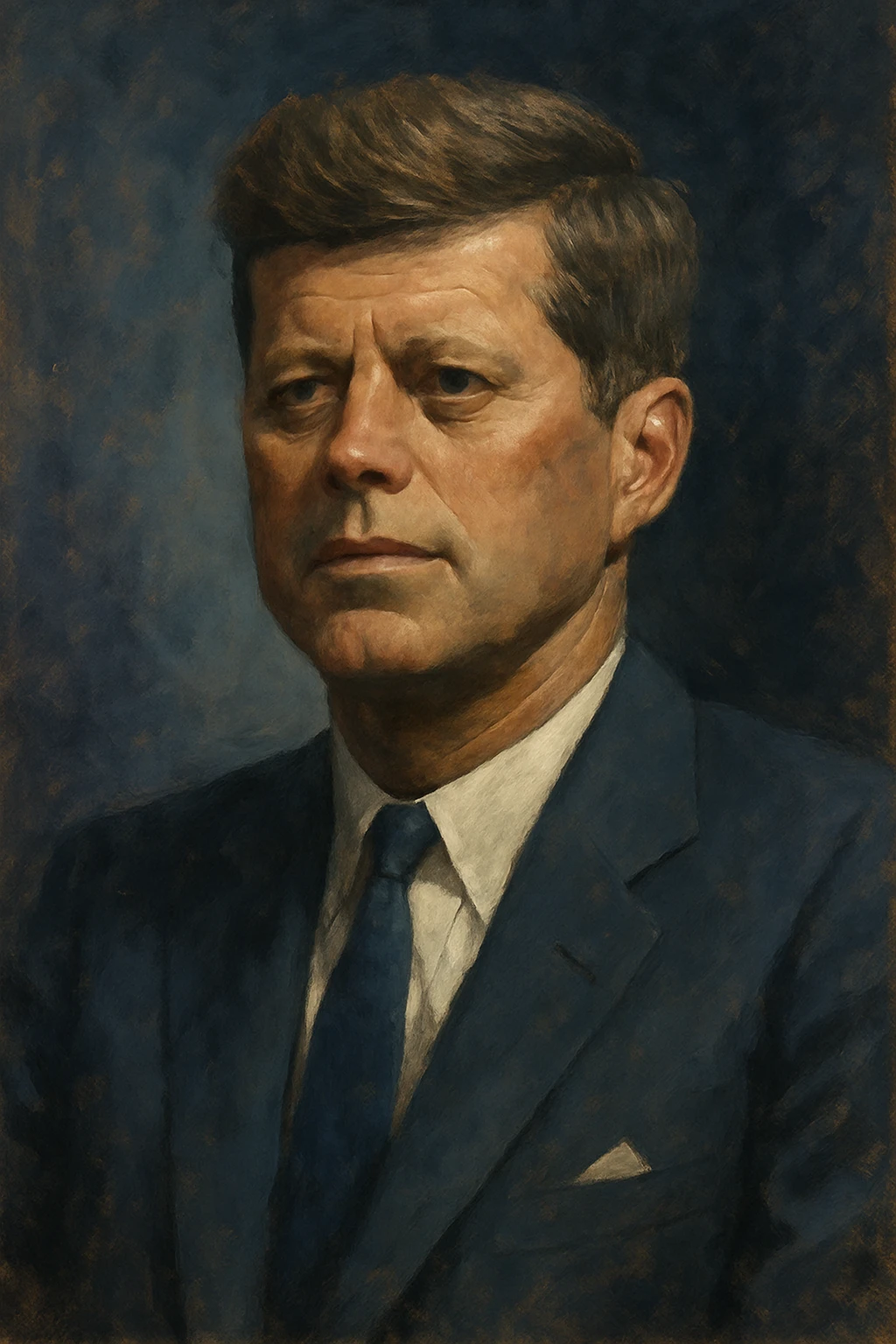

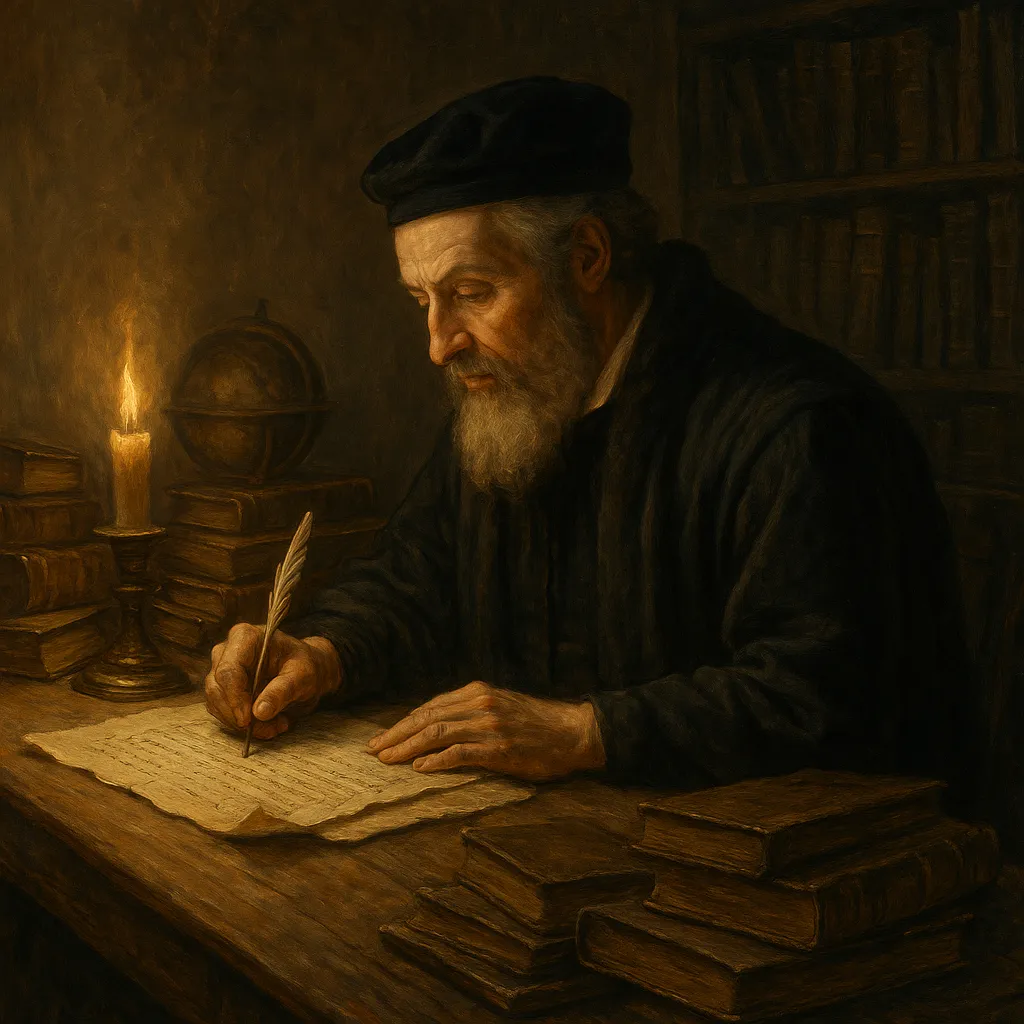

In the 1800s, Englishman Samuel Rowbotham sparked renewed interest in the Flat Earth idea. Publishing under the name Parallax, Rowbotham released "Zetetic Astronomy," a book that claimed to use basic observation and common sense to challenge the globe model. He argued that lakes appeared perfectly level and that distant ships never dipped below the horizon. His public demonstrations and fiery debates drew both supporters and critics.

Rowbotham's efforts inspired others to question official science. Throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, Flat Earth pamphlets circulated in England and America. In 1956, Samuel Shenton founded the International Flat Earth Society, which quickly became a hub for skeptics, religious literalists, and conspiracy theorists. The society ran a popular newsletter, published open challenges to scientists, and even offered rewards to anyone who could prove the Earth's curvature.

Despite jokes and criticism, these societies attracted devoted members and lively public debate. Some members insisted the round Earth was a government hoax, while others simply enjoyed the spirit of questioning mainstream beliefs. The Flat Earth Society grew especially active in the age of televised space launches, using each new mission as a chance to argue their case.

By the late 1970s, the group's popularity faded, but the arrival of the internet gave the movement new life. Today, Flat Earth groups thrive on social media, holding international conventions and drawing attention from both curious skeptics and committed followers.

Famous Experiments and "Proofs"

Flat Earth believers have a long history of staging bold public experiments in hopes of proving their claims. The most famous is the Bedford Level Experiment, begun by Samuel Rowbotham in 1838. On a six-mile stretch of straight canal in England, Rowbotham tried to show that a small boat would remain visible at water level, supposedly disproving the expected curvature of the Earth. When the boat stayed in view, he declared victory and made the experiment central to Flat Earth arguments.

However, later scientists and surveyors pointed out that Rowbotham's test ignored key details, like atmospheric refraction, which can bend light and make distant objects appear higher than they actually are. Newer versions of the Bedford Level Experiment, done with more precise equipment, showed that the curvature of the Earth really can be measured across long, flat stretches.

Modern Flat Earthers continue to rely on similar experiments and visual tests. Some photograph distant skylines or mountain ranges, claiming that objects visible over many miles could not exist on a curved surface. Others point to airplane flight paths that seem strange on a globe but make sense on a flat map. Water level and spirit level tests across lakes and large bodies of water are also popular, as are videos showing supposedly "flat" horizons from high altitudes.

Despite repeated efforts, none of these experiments have provided solid evidence for a flat Earth. Most rely on misinterpreting results, overlooking physical laws, or ignoring standard explanations. Still, the story of the Bedford Level and other classic "proofs" continue to inspire new generations of believers and keep the debate alive in both online forums and real-world events.

Flat Earth Goes Viral

With the rise of the internet, the Flat Earth movement found a whole new audience. Starting in the late 1990s and exploding in the 2010s, online message boards, YouTube channels, and social media groups became gathering places for believers and the simply curious. Videos claiming to expose "the globe lie" racked up millions of views. Arguments once limited to pamphlets and local debates now reached a global stage almost overnight.

Many Flat Earth communities use slick graphics, slow-motion balloon footage, and dramatic music to make their case. Some create detailed animations showing the sun and moon circling above a flat disk, while others analyze NASA photos, looking for mistakes or inconsistencies. The idea that all governments and scientists are hiding the true shape of the Earth fuels endless discussion and speculation.

Celebrity endorsements have also kept Flat Earth in the spotlight. A few athletes and musicians have openly questioned the globe model, sometimes sparking heated debates on talk shows and social media. High-profile stunts like "Mad" Mike Hughes's homemade rocket launches, intended to reach the edge of space and capture photographic proof, made headlines around the world.

Today, international Flat Earth conventions attract speakers and guests from dozens of countries. Some events feature lectures, merchandise, and hands-on experiments. Even with growing skepticism and criticism, the movement continues to thrive online, with new videos, podcasts, and conspiracy documentaries appearing every month. For some, Flat Earth belief is now as much a social identity as a scientific claim.

What Science Actually Says

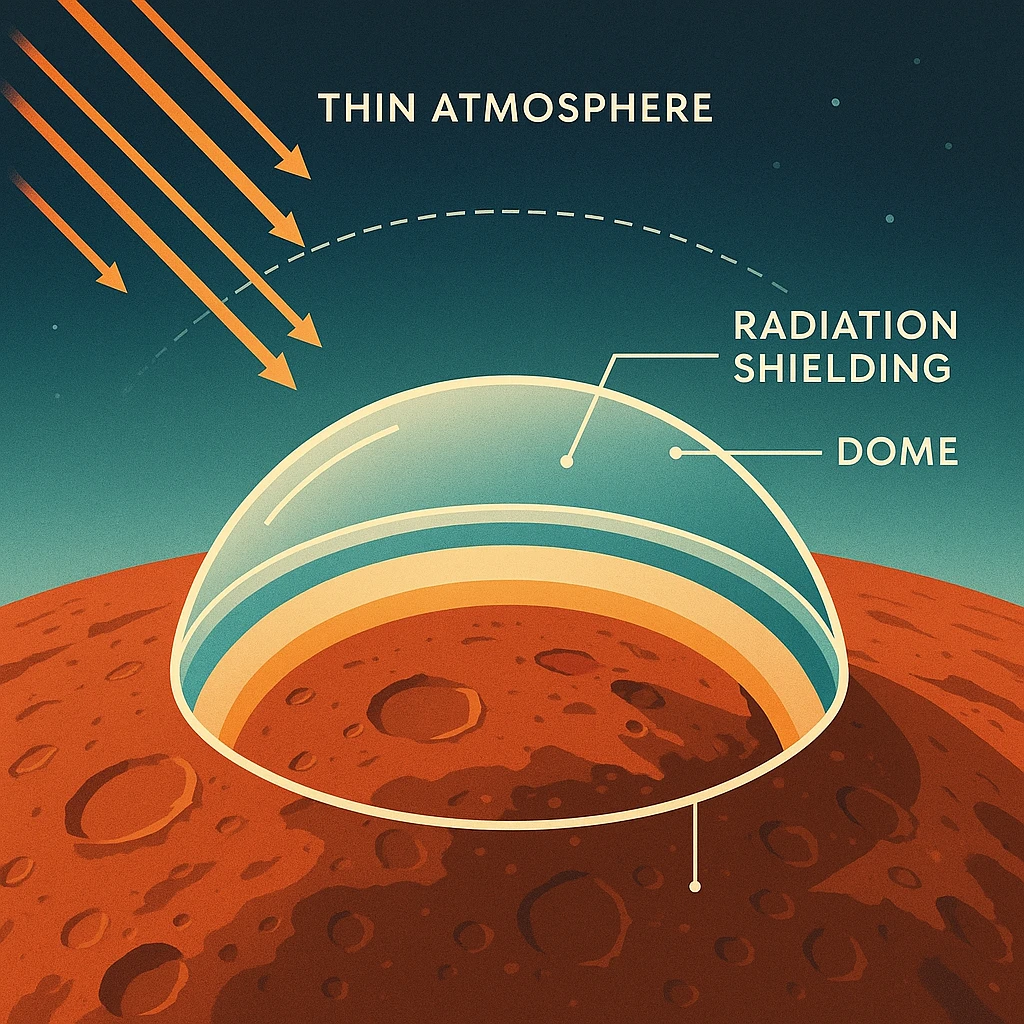

The evidence for a round Earth has built up for more than two thousand years. Ancient Greeks noticed that ships disappear hull-first over the horizon and that the Earth's shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse is always round. Eratosthenes, a Greek mathematician, calculated the planet's circumference by measuring shadows in different cities-an experiment still repeated in classrooms today.

In the modern era, satellite images, international flight paths, and global communications all rely on the globe model. Astronauts in orbit and travelers on long-distance flights have circled the planet countless times. Gravity, weather patterns, and even the way GPS navigation works all depend on Earth being a sphere.

Science communicators note that most Flat Earth experiments misunderstand or ignore well-known physical laws. For example, atmospheric refraction can cause distant objects to appear higher or lower than expected. Photographs of the "flat" horizon from high altitudes miss the fact that the Earth is huge, so the curve is subtle unless viewed from very far away. Rather than disproving the globe, most Flat Earth "proofs" reveal gaps in observation or an unwillingness to accept scientific explanations.

The Enduring Mystery

The real puzzle is not the shape of our planet, but why some people keep fighting for the Flat Earth theory. Social scientists and psychologists suggest a range of reasons. For some, it is a matter of personal identity-a way to stand apart from the crowd or join a close-knit community. Others find comfort in simple explanations or prefer a world where hidden truths can be uncovered by anyone, not just experts.

Distrust of authority plays a huge role. In an age when official stories and science can seem distant or even hostile, alternative theories offer a sense of control. The rise of the internet has made it easy to find like-minded people, building entire communities that share doubts and spread new arguments. For some, Flat Earth belief is less about geography and more about questioning mainstream thinking-sometimes just for the sake of rebellion.

In the end, Flat Earth theory survives not because of strong evidence, but because it speaks to deep human desires: to belong, to challenge authority, and to believe in something different. That may be the greatest mystery of all.